Editors Choice

Personal favourites from over the years. A recommended read!

by - Judie Weedon

MEMORIES OF SCAT

LERWILL

Affectionately known as Farmer Will

Lower Rowes was farmed by my great-grandfather, Joseph Bowden, followed by my grandfather, Samuel Bowden, who then moved to Ruggaton. I think Farmer Will took over the tenancy or bought the property when the Watermouth Estate was sold in the early 1920's.

His wife never enjoyed good health and was rarely seen in the village. She died at a young age. They had no children and he worked the farm alone with the help of his faithful pony and a large cob.

He was a good farmer and gardener but as the years advanced, his health declined until he was not able to look after the farm as he always had. When he was too ill to look after himself, he went to live with his nephew Melvyn Tucker at West Down, but died shortly afterwards.

Most people who remember Farmer Will have an image in their mind of an oid man, short in stature with twinkling blue eyes, sat on a 'tetty' sack astride his pony, plodding up to the village and home again, with 'dug' in tow.

He would tether the pony in Great Oaklands at Turnrounds and make his way to the pub for his Guinness. He would then collect his pony and walk it down to the footpath across Little Oaklands, from which he could launch himself on to the pony's back with the instruction, "Homewards". By the time he reached The Rocks, his eyes were closed and his chin on his chest to all appearances fast asleep!

Most evenings would find him sat on the corner bench in The Globe, with Jimmy Huxtable, Jan Hockridge and my father, Leonard, discussing [sometimes arguing] about the pros and cons of the farming world, in a broad Devon dialect which sadly is rarely heard anymore and would certainly not be understood by most of the patrons of The Globe today!

He some times referred to his horse as his 'scooter'. One day Tim Gubb gave him a lift on the back of his motor bike. At each turn in the lane, as the bike leaned over, Farmer Will was shouting, "Hold the be.... een boy!"

As a younger man he went to Blackmoor Gate and bought a pig. He tied the pig to a drainpipe outside the Top George whilst he went for his Guinness. When he came out, pig and drainpipe had disappeared! He also enjoyed an evening out at Hele Bay with Parky Smith and Clifford Passmore. The pony also knew his way "homewards" via Goosewell from there!

On New Year's Eves he was persuaded to sing. He had a lovely clear voice and sang old local dialect songs - what a pity no one had the foresight to record these.

Dear old Farmer Will, fondly remembered.

Michael B

Lower Rowes Farm taken c1970 [from the north, the opposite direction to Tom's postcard] before being restored by the late Mr. & Mrs. Bill Tyrrell.

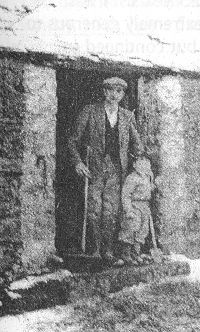

Will Lerwill on his pony - with 'dug' in tow - at the junction of Jan Bragg's Hill, The Lawn and Wood Park Lane.

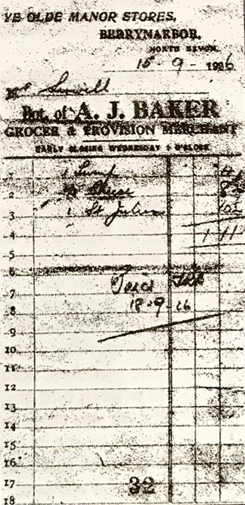

Farmer Will's weekly grocery bill from the Manor Stores, 15th September 1926. 1 lump [salt], cheese and his St. Julien 'baccy'.

Photos and bill

kindly shared with us by:

Brian and Viv Fryer - Lower Rowes

15

MY LIFE ON THE

FARM

Ron Toms

I was born Ronald Francis Toms at Middle Lee Farm on 15th July 1916. Middle Lee was the home or my grandparents Frank and Ellen Toms - which was then a working farm of about 80 acres.

1. Frank and Ellen Toms - my grandparents - at Middle Lee.

At that time, Frank and Ellen [nee Petherick] served proper Devon Cream Teas - when dry on the lawn in front of the farmhouse and when wet in the barn bordering on the road now converted to be part of the farmhouse. Horse drawn coaches with visitors would come over from llfracombe for afternoon teas. They would sometimes come down Smythen Hill and go back over Hagginton Hill; at other times they would reverse the journey. When going downhill, the coaches would be held back with wheel drags. Nervous passengers often opted to walk down the hills. When going back up hill, some passengers asked to walked again, and at times they would all be asked to walk. Mrs. Richards [Lorna Bowden's great-grandmother and Lorna Price's grandmother] would bring lavender to sell to the visitors.

After Frank and Ellen died, Middle Lee was farmed by Dan and Lizzie Toms and I lived with them, my cousins Reg and Vi, and my mother until she married Jack Geen.

I attended Berrynarbor School between the ages of 4 and 14 years, and when I was old enough, delivered milk around the village before starting school. School began at 9 o'clock when the bell in the tower would be rung, often by one of the pupils. [The tower remains, but there is no bell today.] Those pupils delivering milk were allowed an extra half-hour and we were expected to attend by 9.30 a.m. I would have two large cans of milk - 1 skimmed and 1 fresh milk - and would ladle it out with a pint jug into the customers' jugs. At week-ends there would also be Devonshire cream to deliver.

Whilst I was at Middle Lee, PC Abrahams was the village Policeman. He lived at No. 16 Henton Hill and when on duty he could always be found somewhere around the village. I remember that when the other lads and I were up to no good, we always disappeared fast when PC Abrahams appeared!

In those days, if you were ill and needed a doctor, you had to ride to Combe Martin to fetch one, and then together with him ride back to the village to the patient. The doctors Manning - both husband and wife were doctors - lived near Church Corner. He rode a black horse, and she a white [grey] one.

When I was about 10 or 11, I moved with my mother, Hilda Toms, and my step-father Jack Geen to 23 Henton Hill - this is what Haggington Hill was called at that time. Jack Geen's real name was George Henry Geen, but when working for a farmer who was also called George, the farmer changed his name to Jack! But the Revd. Churchill always called him John!

Jack Geen was a hard taskmaster! When I returned from school and in the school holidays and at week-end, I would help him in the garden and also cut logs in the shed in the garden for using in the house. We would also, helped by another man, work on the roads all round the village, clearing the sides and putting the rubbish into piles, which would be collected and taken away, usually in a horsedrawn wooden farm butt, often by Len Dummett who was then working for Claude Richards at Hammonds Farm.

On wet days we would wrap up against the weather and with shovels would clear the drains. We also dug stones at the Sawmills Quarry, which was on the left of the main road, just above the entrance to what is now Napps. The stones were again loaded on a butt and taken to depots around the village. One stone depot was at Mill Park, now used as a passing place on the road [it was not a layby]. There was also a depot up Smythen Hill. Once in the depots, the stones would be cracked smaller into chippings.

2. Scythe cutting the field west of Barton Lane [below Red Tiles and Byways], with Stanley Harding [Horseman],

sheepdog, Ben, and horses Duchess [right] and Tidy [left].

(The little boy is John Willis, Bob Richards' cousin, who came especially to have his photo taken!)

My father and I would also help make up the roads. Water, in a horse drawn water cart, would be mixed with the stones and earth and then rolled with a steam roller.

When I was 16, I went to work for Fred Richards and his wife Emma at Home Barton Farm. New jobs nearly always commenced on Lady Day, 25th March, and on that day I began my duties at the farm, taking with me my tin box of clothes.

I 'lived in' at the Farm, as a member of the family, for some 10 or 11 years, almost until the time I was married. Fred and Emma had 7 children, so with me, 10 of us would sit down to every meal. Every day we had three meals and would all sit down together. There would always be meat, large joints which Fred would carve, and dishes of vegetables to which we helped ourselves. Emma used to bake her own bread and make her own butter. The butter was kept cool just inside the well in the garden, where a cupboard, with a stone slab and a door had been placed on a shelf just below the top of the shaft. The cream was also kept cool here, but due to demand never stayed long! Emma did not sell her butter.

My first job was to hand milk the cows twice a day and then deliver milk around the village and Combe Martin, together with some of Fred's children. Then the yard would need to be cleaned and the cows fed. There was no machinery and the barns were only sheds. There were no tractors and the work was done with forks and spades. There was always hoeing to be done in the fields, often helped by casual labourers and also members of the family. The farm routine had to be done day-in and day-out, year-in and year-out.

The sheep and cattle fodder was grown on the farm, as was the feed for all the animals including pigs and poultry. At special times, like harvest and potato lifting, helpers would come from other farms and in turn those working at Home Barton would go and help out on their farms. When the coal vessel, the Snowflake, came into Combe Martin, we would also go down to help unload the coal and there would be as many as 5 or 6 horses and butts from other farms. The coal would be taken by horse and cart from the boat - the horses did not like working on the beach, and were startled when the first batch was unloaded on to the cart - to the Cross Street yard of Mr. and Mrs. William Laramy, where it would be weighed into hundredweight bags and then delivered by horse and cart to Combe Martin, Berrynarbor, Berry Down, East Down and Arlington.

3. With Michael Richards in the snow.

When I started working and was 'living in', I earned 18 shillings a week. Horseman was a most important position, and this was held by Stanley Harding when I began working, but by the time I finished working at Home Barton, I had risen to the dizzy heights of Horseman myselfl I remember the horses with affection - Tidy, Duchess, Prince and Darling amongst others. Whilst I was at school, Dunchideock House [as it is now] was, before it was Claude Richards' dairy, Samuel Harding's wheelwright premises, and his blacksmith forge was on the opposite corner below Little Gables. Following Samuel Harding was Harry Camp, who moved the smithy down the hill to what is now Forge Cottage. However, by the time I was working at Home Barton, both premises had closed and the horses had to be taken to Combe Martin to be shod.

Whilst 'living in' at the Farm, no work was ever done on Sundays except the milking. Sheep and cattle feed would be put out in adjoining fields on the Saturday and on Sunday the animals would be allowed into the next field! The family, and l, would attend the Combe Martin Methodist Church twice on Sundays, where I still go to this day.

During the wintertime, about 30 young men and lads, including myself, would meet once a week for Bible Study Group with the Revd. Churchill in the Parish Room at Turn Round, opposite the Rectory entrance. [The Parish Room now forms a classroom for the Primary School.] We would meet from about 7 o'clock to 8.30 or 9 o'clock and each of us had our own Bible and in turn would read a verse. The others often made excuses not to read, and so I would read for them. We were all given a church leaflet entitled 'Ashore and Afloat'.

Every year, the Bible Study Group was treated to a Christmas Supper, a good meal with Christmas pudding for afters! This would be brought over to the Parish Room in a wheelbarrow and one or two of the domestics from the Rectory would wait on us.

Before attending the Bible Study Group, I had been a member of the Sunday School and Church Choir. Sunday School in those days was held at the Primary School and in the summer we would be invited to the Rectory for a picnic. Each child would take a mug and sandwiches and cakes would be brought out to us. At that time the Rectory garden was bigger, extending to the curved wall opposite Rock Bottom, and was tended by two gardeners, one of whom was Dick Richards, Lorna Price's father, and the other possibly Charlie Huxtable. Ernest 'Ern' Richards was the coachman, driving the horse carriage and later the motor. He was the grandfather of John Huxtable and Betty Brooks.

If children, especially the boys, misbehaved in school, the Revd. Churchill had to be brought over to rebuke them, but he was not a firm disciplinarian and often just said, 'Boys will be boys'!

Life at that time was not all work and church, there were the dances at the Manor Hall! These would finish about midnight and then often we lads had to walk the young girls back home to Combe Martin. We would often meet up again before returning to Berrynarbor, but we would all be at work early the next morning!

Following my marriage to Gladys, I continued to work on the farm when we were living at 16 Henton Hill before moving to Birdswell Lane. Emma Richards was always extremely generous to us, giving us meat, bacon, cream and other produce to take home at week-ends.

Sadly she died whilst I was working for Fred, which I did for 30 years. Following Fred's retirement when he moved to Sherrards in Barton Lane, Home Barton Farm was worked by his son Bob and his wife Betty. I carried on with the same jobs and worked for Bob for another 23 years. I was always very happy working for both families who were extremely generous to me and my family. I retired when I was 70, in 1986, but continued to help out as and when extra hands were needed. I have always received a Christmas present and continue to do so to this day.

Ron Toms

Ron says that hard work on the farm never did him harm! Certainly, as he approaches 87, he is still fit and active - long may that remain so. His motto: Wear Out, not Rust Out!

Thank you, Ron for sharing your memories with us, for all that you do around our village, but most of all for being you!

32

HOW TO GIVE A CAT A PILL

Pick up the cat and cradle it in the crook of your left arm as if holding a baby. Position the right-hand forefinger and thumb on either side of the cat's mouth and gently apply pressure to its cheeks whilst holding the pill in the remainder of the right hand. As the cat opens its mouth, pop the pill-in and allow the cat to close its mouth and swallow.

Retrieve the pill from the floor and the cat from behind the sofa. Cradle the cat in the left arm and repeat the process.

Retrieve the cat from the bedroom and throw the soggy pill away.

Take new pill from foil wrap. Cradle cat in left arm, holding rear paws tightly with left hand. Force jaws open and push pill to back of mouth with right forefinger. Hold mouth [cat's] shut for a count of ten.

Retrieve pill from goldfish bowl and cat from top of wardrobe. Call spouse from garden.

Kneel on floor with cat wedged firmly between knees, holding front and rear paws. Ignore low growls emitted by cat. Get spouse to hold head firmly with one hand whilst forcing wooden ruler into mouth. Drop pill down ruler and rub cat's throat vigorously.

Retrieve cat from curtain rail and unwrap a fresh pill. Make note to buy new ruler and repair curtains. Carefully sweep shattered figurines and vases from hearth and set to one side for gluing later.

Wrap cat in large towel and get spouse to lie on cat with head just visible from below arm pit. Put pill in end of drinking straw, force open with pencil and blow pill down drinking straw.

Check label to ensure pill is not harmful to humans. Drink a beer to take the taste away. Apply a Band-aid to spouse's forearm remove blood from carpet with cold water and soap.

Retrieve cat from neighbour's shed. Get another pill. Open another beer. Place cat in cupboard, closing door on its neck so that the head is only showing. Force mouth open with a desert spoon. Flick pill down throat with elastic band.

Fetch screwdriver from garage and put cupboard door back on its hinges. Drink beer. Fetch bottle of Scotch. Pour and drink. Apply cold compress to cheek and check records for date of last Tetanus jab. Apply TCP compress to cheek to disinfect. Toss back another Scotch. Throw T-shirt away and fetch a new one from bedroom.

Call the fire brigade to retrieve cat from tree across the road. Apologise to neighbour who demolished fence whilst swerving to avoid cat in road. Take last pill from foil wrap.

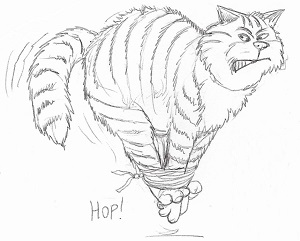

Tie the little bastard's front paws to rear paws with garden twine and bind tightly to leg of dining table. Find heavy duty pruning gloves from shed. Push pill into mouth followed by a tin of tuna chunks [his favourite]. Be rough about it. Hold head vertically and pour copious amount of water down throat to wash down pill and tuna.

Consume remainder of Scotch. Get spouse to the nearest A&E unit and sit quietly whilst medic stitches fingers and forearm and removes remnants of pill from right eye. Call into furniture shop on the way home to order new table. Arrange for RSPCA to collect mutant cat from hell and see if they have any hamsters.

HOW TO GIVE A DOG A PILL

Wrap it in bacon!

Illustrations by: Debbie Rigler Cook

31

A LETTER OF THANKS

to the Village of

Berrynarbor & It's Friends

As many of the villagers know I have been working in Malawi for the past year and a half. Many of you have sent donations of money, cuddly-toys, baby-clothes and blankets which I have had a lot of fun directly distributing. I hope this article will show you how your generosity has really made a difference to some of the Malawians that I have met.

First a bit of background...

Malawi comprises a narrow strip of land about 119,000 sq Km in area wedged between Mozambique, Zambia and Tanzania. It has a population of approximately 10 million. It was recently ranked 169th out of 179 countries in a World Health Organisation health standards survey. Two out of five children do not survive to their fifth birthday and the average life expectancy, which is falling sharply, is between 35 and 40 years. Health problems are largely related to poverty and malnutrition, immunocompromise (HIV/AIDS), and infectious diseases (Malaria, TB, and diarrhoeal illnesses.) Trauma and complications of childbirth also contribute to the workload in all hospitals. Countrywide shortages of qualified staff, basic equipment and drugs hamper health service delivery. Insufficient and delayed investment in infrastructure further exacerbates this problem. The country has an annual income of approximately $705 million, of which $260 million comes from international donors. To put this in perspective, its annual income is about a third of the amount spent by a large pharmaceutical company on drug research and development each year. Malawi spends approximately $763 million a year of which $40 million goes on health. Most of this $40 million is spent on drugs. There is a lot of corruption and it is claimed that 60% of the medicines purchased 'disappeared' from government hospitals last year. Health care is provided by village health centres and dispensaries, together with community and district hospitals, and the central hospitals in Blantyre, Zomba, Lilongwe and Mzuzu. Around 30% of rural health care is provided by church charitable organisations.

Villagers often have no income and survive only on what they can grow. As you will have read in the press, recent weather conditions in Malawi have resulted in a dramatic fall in the yield of the staple food Maize. The government has not made up the shortfall (its reserves were sold for cash to other countries last year) and so millions of Malawians face malnutrition and starvation. In small towns and villages across Malawi there are queues of people lucky enough to have some money and hopeful of buying maize.

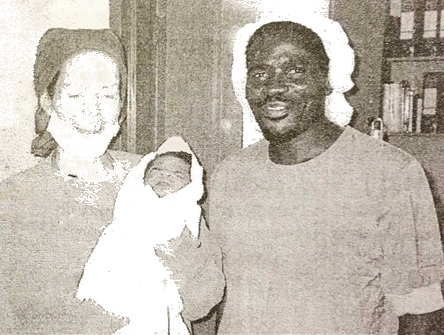

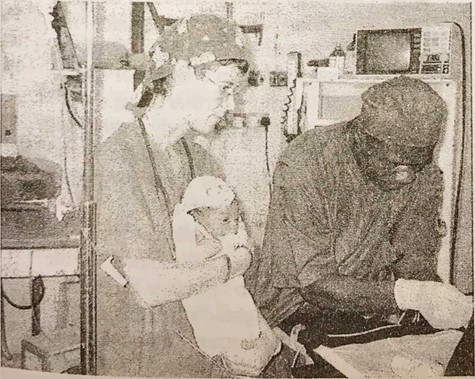

Mr. Lingo, a Malawian doctor, trained by Mary,

with an American volunteer midwife

There are other queues at feeding centres where international aid agencies have moved in to distribute food. The international effort is impressive but it can't reach everyone, the vulnerable slip through the net. Orphans, elderly folk struggling to care for their orphaned grandchildren and the sick simply can't make it from their remote villages to take advantage of the rations.

Now, imagine you are a Malawian living in a remote village where the crop has failed. When you become sick you would first consult the village 'African Doctor'. Some of their remedies are very powerful, and some of their patients do recover. If your illness gets worse, however, your family will probably take you to the nearest community health centre for 'injections' (Western medicine). Unfortunately these health centres have almost no facilities or medicines but they are close enough to home that your family can visit you, bring you food and nurse you under the watchful eye of a medical attendant.

If you are still getting worse and your condition is obviously serious, your family are faced with a very difficult decision. Should they leave the village (and all their many dependants) and try to take you (at immense expense on the back of a truck, or roof of a lorry) to a bigger hospital in the hope of a cure, or, should they simply accept that you will die and concentrate on looking after their other relatives. It's a tough one. If they think you have a chance and you survive the journey, you will arrive at the central hospital probably already at death's door, proper treatment may have been delayed too long, you'll have travelled hundreds of miles in the heat without food or water, you'll be weak and will now be completely abandoned by your family who can not afford to stay. They have no money, no source of food in the city and a distant family to look after. They have to go home. On a good day you'll be seen and treated quickly by a clinical officer or doctor, on a bad day you'll be one of 250 admissions and won't get seen, or the drugs you are prescribed will turn out to be 'out of stock'. You'll get a bed on the ward or maybe just a space on the floor between the beds. There will be 100 patients crammed into the ward with 60 beds and just one nurse. She can't possibly nurse everyone and since you have no relatives with you, you won't get food or drugs. If you need an urgent operation you'll join a queue outside the operating theatres lying on the floor or on a hard metal trolley. If you need a blood transfusion you won't get one because you have no relatives around to donate blood. After the operation you'll be taken back to the ward with little chance of getting any painkillers. If you are lucky you'll get antibiotics and a drip, but only if the hospital hasn't run out. This situation is the same even if you are a baby or a small child. It's the same if you are a pregnant woman in obstructed labour or bleeding after a miscarriage. Amazingly, many patients survive the ordeal and return to their villages, but it's a grim lottery and explains why many Malawians see western medicine as a last resort.

Due to lack of space, two babies - not twins - in one cot!

I am an anaesthetist (a 'gas-man'!). I worked at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), the largest hospital in Malawi. For six months I ran the intensive care unit and for another year I ran the anaesthetic service in the maternity theatres. It was very busy; emergencies were being rushed in 24 hours a day. I had to do the job and train students from other hospitals all over Malawi to become anaesthetists. It was stressful, often very frustrating, but also very rewarding. As I settled in I realised there were some simple things that could be done to give the patients a better deal.

When my mum phoned one evening and said that people in Berrynarbor were asking if there was anything they could do, I didn't realise how much help was coming our way.

The first things to start arriving from Berrynarbor were baby clothes. It might seem a bit odd worrying about hypothermia in Africa but it's a big problem for newborn babies, especially the premature and sick ones. You sent us hundreds of bonnets and baby-grows and by recycling them we were able to clothe every baby born by caesarean section in the operating theatres. We let especially needy mothers take their baby clothes home. They were a bit surprised and some couldn't quite believe their luck. You also sent loads of baby blankets for wrapping up the babies as they waited for their mothers to recover from anaesthesia. I sent some of the blankets to the special care baby unit. Next several consignments of cuddly toys arrived. I sent some to the intensive care unit to cheer up the kids recovering from operations, and some to the children's wards and nutrition stations. We kept some in theatres for distracting little ones while we were trying to give them injections and anaesthesia. Along with the small baby things came some clothes for Older babies. I took those down to a local orphanage that cares for infant Orphans. It's called 'Open Arms' and is run by a British couple called Rosemary and Neville. They have their hands full with about 35 babies many of whom have contracted HIV from their deceased mothers. Rosemary and Neville were very grateful to receive such good quality nearly new baby-grows.

Money started arriving, some of it from personal donations and some from fund-raising events in Berrynarbor, and beyond. I bought 40 baby mattresses for the special care baby unit and around 20 bigger mattresses; enough to make sure that every patient recovering from anaesthesia and surgery could do so in comfort. I bought 20 thick blankets to cover patients after operations. Anaesthesia blocks the body's normal ability to stay warm so the blankets give the new mothers a lot of comfort. We had an epidemic of Cholera and suddenly had hundreds of children and babies coming to the hospital with severe dehydration. The hospital quickly ran out of drips for the small children but I was able to buy enough to see us through. Later in the year the Malaria season brought us over a hundred new children a day, all needing drips. Again, I was able to buy the equipment needed. Our hospital only provides a few basic antibiotics, and many of the infections we treat are resistant to them.

Mary holding a very new-born baby that was crying with no one to look after it, whilst instructing a student doctor, Mr Kunje, on how to give a spinal anaesthesia for an imminent caeserian.

A more modern antibiotic called Ceftriaxone is available in Malawi but is too expensive for the hospital to buy. Many children die every week because they don't get this treatment for meningitis, septicaemia and pneumonia. I was able to buy a huge supply of ceftriaxone for the children's department to use over the next year. One of the student anaesthetists who we had been training for 6 months started to lag behind the class. We realised that after a recent bout of meningitis he had become very deaf and was finding it impossible to work safely. His base hospital was depending on him returning after his training to be the only anaesthetist in that area. Without him there would be no emergency caesarean sections and women and their babies would die in childbirth. With money you sent I was able to buy him a second hand hearing aid and he should graduate to serve his community in April this year. In his career as an anaesthetist he will save hundreds, maybe thousands of lives by getting patients safely through operations. A good investment I think!

One of our student anaesthetists sadly died of HIV/AIDS. Some of our department went to his funeral, which was at his home village at the very southern tip of Malawi on the Mozambique border. It was a difficult journey, the road finished long before we reached the area. We found villages there that had been devastated by floods in recent years and were now suffering crop failure due to poor rains. People were starving and we discovered that our student had been one of the only wage earners in his whole village. He had been sending almost all his wages home. The village chief and his family were distraught at the loss of their son and their only hope. With some of the money you sent I was able to load up a vehicle with essential food supplies and go back to the area. We gave some of the food to his immediate family and another larger supply to the village chief to distribute amongst the village people. I met with the chief; and was invited to sit with him on a small stool under a huge tree in the middle of the village. After many traditional greetings and introductions he said I should take a message back to my home. He asked me to thank the donors who had never met his people but had given them so much.

On behalf of all the Malawians who have enjoyed your generosity I would like to thank everybody in and around Berrynarbor who has contributed in any way. I hope this article has shown you how much comfort and hope your gifts have given. More than that, you have simply saved hundreds of lives.

Note. The babies in all the photos are clad in clothes and blankets from Berrynarbor,

Thank you.

Dr Mary O'Regan - Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Malawi

34

THE STERRIDGE OTTER

Our story starts ...

Mid afternoon on Friday, 2nd January, I was working in the garden at Riversdale when I perceived a movement out of the corner of my eye. Moving along the wall which runs parallel to the driveway, was a small animal, about eighteen inches in length and mainly dark brown in colour. I did not know what sort of animal it was, although it was obviously very young. I had no idea what a young badger or mink looked like, in fact I felt quite ashamed that although I take a very keen interest in wild life, I could not guess what it was. It moved further along the wall until it reached a point where it either had to turn back or try to get down from the wall. It chose the latter and performed an almost perfect somersault on to the driveway. It did not appear to have suffered any injury and moved under the car where it stayed. I called for Jill to come and see it and bring my camera, which she did very quickly, although the little animal was even quicker and moved from under the car to the cover of shrubs. It was so well concealed that we could not see it, nor take a photograph, which was disappointing.

Sterridge in the arms of one of her many carers

After a few minutes, the little creature started to make a very shrill cry, making me aware that it was almost certainly calling for its mother and I decided to make myself scarce in case the mother was close by and waiting for the opportunity to rescue its offspring. I kept a watch until it was going dark, but there was no sign of the mother and I decided that I was perhaps too close and went into the cottage.

Later that evening, I went out to see if anything had happened and to my delight there was no sign of the little thing, so I returned indoors believing and hoping that the baby had been rescued by its mother and had returned to its home.

The following day, as we were having lunch, and for the second time in two days, I was surprised to see the same little animal padding along the road coming over the bridge. Again, I called for Jill to come and see but at the same time noticed Rosie, our neighbours' springer spaniel, running towards it, whereupon I rushed outside as fast as I could. Fortunately, Pat was nearby and immediately called to Rosie to "Stop!" To her great credit she did. "It's an otter," shouted Pat, which did several things to me all at once. The main thing, however, was the realisation that she was absolutely right and what the heck was an otter doing in the Sterridge?

Meanwhile, the little creature had turned into the small riverside Garden belonging to Brookvale, had gone into the undergrowth and was in danger of going into the very thick hedge, from which it would be very difficult to recover without injury. Fortunately, at this point June and Bernard from Pink Heather walked by and I was joined by Malcolm, allowing Pat to go and ring their close friend, David Chaffe, the otter expert.

Bill Jones

it continues ...

On that beautiful Saturday lunchtime, I had arranged to collect Emma from Smythen Farm Cottages and from there we were heading for Woolacombe Bay and a walk with Rosie. On the way to the car, imagine my surprise and delight when I saw a baby otter on the lane outside the cottage.

By the time I had 'phoned our friend, David, for advice, we had been joined by Janet and Judie. Acting on David's advice, we were able to get the otter into a cat basket provided by Judie. In the meantime, David had contacted the vet at Torbridge Veterinary Centre to expect our otter within the hour. He and I agreed to meet half-way between here and Bideford.

Emma was waiting for me at the top of the Valley. I can't begin to tell you how I felt. During the journey, Emma asked lots of questions about otters and we talked about the baby we had on board. I quietly prayed that its life would be saved.

As arranged, half-an-hour later, we met David and his daughter, Olivia. Quickly the baby otter was transferred to their car and away they sped. Emma and I then decided we would return home for a well earned cup of tea followed by a walk with Rose in the Sterridge Valley, and await news of our baby otter.

Pat Sayer

and goes on ...

Sterridge was a lovely otter, she was swept down the stream in the Sterridge Valley where Bill and Pat found her. Sterridge was what we called her, she was found near a wall just by the stream.

Pat had phoned me up that morning to see if I wanted to go down to the beach with her to take Rosie for a walk, but then Sterridge was found so off we went to Barnstaple to meet David, who knows about and takes care of otters. We all waited for some news on Sterridge, so 3 days later Pat phoned David to see how she was, but sadly she had died. I shall always remember her and was so pleased that I had the chance to meet an otter close up.

Emma Elstone

and finally ...

Two telephone calls later and a travelling box with the tiny cub was speeding to a rendezvous and the Torbridge Veterinary Centre in Bideford. Because the previous night had seen sub-zero temperatures, the veterinary surgeon on call had difficulty in raising the cub's temperature. It was immediately placed on an electronic heating pad to see if a survival process could be initiated. Recovery was unlikely, but care from the nursing staff was on hand and their fingers were crossed.

Forty-eight hours later, the decision was taken to move the cub to the Tamar Otter Sanctuary at North Petherwin near Launceston. There had been some slight improvement but nothing significant and it was felt that the one-to-one support which Mick Sidnell, the Manager of the Sanctuary, could offer, would be the best option.

After a continuing hour-by-hour vigil, however, the cub passed away peacefully at four o'clock the following morning, despite every effort to sustain its life. A close examination confirmed the cub to be a bitch; it also revealed several ticks in the early stages of growth which suggested she had been relatively lifeless for longer than had been previously assumed.

Everyone involved was sad to learn that the little cub had not made it. However, the good news from the occurrence is that it is clear that otters are continuing to recover their numbers after the severe declines they experienced over thirty years from the mid1950's. Sadly, cubs will still come to grief but the professional people are now in place to help, as happened in this case.

Wild bitch otters, on heat every forty-five days and with a 63 day pregnancy, usually give birth to twin cubs weighing around 78 grams each. They can, and do, breed in any month of the year. The mothers will often move their cubs at around six or seven weeks of age to an alternative holt. This little cub, weighing 1060 grams, could well have been one of triplets but could, as well, have been losing ground on its siblings for some time. The mother otter possibly left this cub behind in the original holt.

My first wild otter cub was fetched by a springer spaniel from wet mud on an ebbing tide on the north Norfolk marshes on Boxing Day 1966. The second, Storm, was found by a postman high on Exmoor, eleven years ago this coming mid-February. She weighed only 1 lb 7 oz but survived, just, to become nationally known through her appearances with me at lectures and on film.

Sterridge was only my third wild cub in thirty-seven years, she was also discovered by a springer spaniel. Sadly, her time with us was all too brief. I thought history was going to repeat itself but not this time - third time unlucky. Without doubt, however, there will be others and most of them, for sure, will be blessed with a better share of the luck that all wild otters need.

David Chaffe

We are all most grateful to David for his contribution to Sterridge's story and readers are well advised to read his book about Storm, entitled 'Stormforce'.

In his acknowledgement of the book, Nick Gordon [wildlife film-maker] says: 'If there is anyone who can read the mind of an otter it is David Chaffe. During twenty years of making wildlife films, I have not met anyone more enthusiastic or knowledgeable about our Country's most endearing creature. This personal and touching story is simply delightful.'

37

FARMER UGGETT

Further Verse in

Devonshire Dialect

THE WIFE'S JACKDAW

The missus ed a jackdaw, tame?

Ur found this zoaked bedreggled chick-

I should'a ringed iz ruddy neck.

Ur dried un off an saut un up

An ed'n drinkin out a cup.

The dug wuz ordered out the ouze

An I wuz told t'shut me face.

Ur though the worlds of thic there burd

Sich silly talk y' never yered.

"An oo's iz Mummy's darlin Jack."

Yuk - twere anough t'make ee sick!

With thic there ruddy burd out loose

I couldn't sup a jar in peace.

Ee'd keep on swearin, gitt'n louder

An so l'd ev t 'share me cider.

All up and down the table top.

Ee'd cock iz aid one side an wait

Fer aff a chance t' rob me plate.

Ur made a master fool of ee

Like what ur never makes o'me

An if I ast fer jackdaw roast

Ur'd say ur's married to a beast!

Th'ol thing, ee used to squawk like ell-

Jus like a fire engine bell.

One time I sellotaped iz beak

So's I could yer me own sulf spaik.

Ee used t' perch right on me shoulder

An then ee'd drop a gurt big bolder.

An when I jus cleaned up me jacket

Ee'd cetch me wiv another packet!

T' shop fer vittles in the town.

Ur id the sellotape out back

An lef me babysitt'n Jack.

No sooner ed ur left the ouze

When Jack starts kickin up a fuss.

There's me all set t'watch the match,

An ee all set t 'make a spaich!

"You evil little burd!" I sez,

"A nasty piece o' wurk you is."

I upped and fetched a jar o' juice

Cuz shout 'n weren't no ruddy use!

Twuz like I'd turned the wireless off -

Ole Jack went quiet sure anough.

Ee sidles up an climbs me jar

An ulps izulf t'cider there.

I feels mesulf all gitt'n soft.

An so I let 'n bide - why not.

An fills mesulf another pot.

The match wuz good - our lads wuz game

An then I yers the missus ome ...

Next thing ur starts t' rant an rave,

An screams fer me t' pack an leave!

Twuz then me 'eart felt proper bad ...

Cuz there wuz Jack stood on iz aid

Wiv tail stuck up frum out the jar

Ee'd leaned in just that bit too far!

Now, cuz I want to keep me wife

I gives th'ol thing the kiss o' life.

First time y' seed a farmer yet

What takes daid birds t' see the vet.

Illustrations by: Paul Swailes

Lynda Waller - Lynda Waller is just completing and publishing her third Farmer Uggett Book of Verse in Devonshire Dialect - the first was Farmer Uggett, the second Farmer Uggett and Plumber Sloath. These booklets, beautifully illustrated by the author, are available at £3.00 each from Kelly Publications, 6 Redlands, Tiverton, EX16 4DH, or telephone Lynda on 01884 259526.

31

FISH

John Cunliffe

fat

cat

swish

fish

purr

fur

wish

fish

paw

below

dip

flip

mouth

wide

fish

slip

inside

lips

lick

cat

nap

Illustrations by: Debbie Rigler Cook

37

A HOME FROM HOME?

How do you get from Lynmouth to Barnstaple? A simple question you might think, but you could be surprised by the answer.

- "At the end of Lynmouth Crescent (1), cross straight over

Dulverton Drive (2) and turn into Buzzacott Lane (3). From there, pass by the turning

to Combe Martin (4). Barnstaple Court (5) is the next turning on the right."

Confused? Well don't be. The answer lies in Milton Keynes, home of concrete cows and infinite roundabouts.

As most people know, Milton Keynes is a new town. As such, the Development Corporation were faced with the difficult task of picking names for the many thousands of new roads. In the end, they opted for a simple solution - pick a theme for an area and name all the roads in the area accordingly.

- Far Bletchley - Haydock Close, Chepstow Drive, Epsom Grove, Sandown Court, Wincanton Hill [Race courses]

- Crownhill - Lennon Drive, Morrison Court, Hendrix Drive, Bolan Close [60/70's pop stars]

- Browns Wood - Mendlesson Grove, Holst Crescent, Schuman Close, Wagner Close [Composers]

- West Bletchley - Tweed Drive, Severn Way, Derwent Drive, Ouzel Close, Mersey Way [Rivers]

- Denbigh - Arbroath Close, Lothian Close, Kinross Drive, Ayr Way, Peebles Place [Scottish towns]

- Water Eaton - Grasmere Way, Buttermere Close, Crummock Place, Windermere Drive [The Lake District]

When choosing the road names for Furzton, the theme selected was North Devon and Somerset. The following are just a subset of the names used:

- Combe Martin, Blackmoor Gate, Challacombe, Simonsbath, Bampton Close, Countisbury, Barnstaple Court, Buzzacott Lane, Brendon Court, Exmoor Gate, Trentishoe Crescent, Withycombe, Arlington Court, Lynmouth Crescent, Porlock Lane, Watersmeet Close, Muddiford Lane.

There can't be many places in Britain that are more different from the Sterridge Valley than Milton Keynes. However, I can still take a drive through Combe Martin, pass by Blackmoor Gate and pop in to Lynmouth, which I guess makes it a real home from home!

James Weedon

29

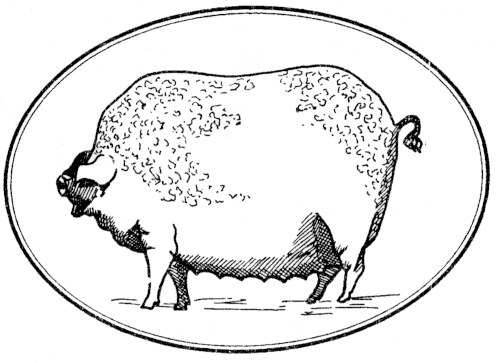

PRIZE PORKERS - PART II

CURLY COAT

The thick curly coat offers protection in these chilly climes. Now extremely rare, this course pig, given the opportunity of unrestrained consumption, will reach enormous weights.ORKNEY BOAR

Resembling a miniature wild boar, this hardy native breed lived in herds and was originally descibred as "a litte monster, savage and voracious but no larger than a good sized terrier."

ULSTER WHITE

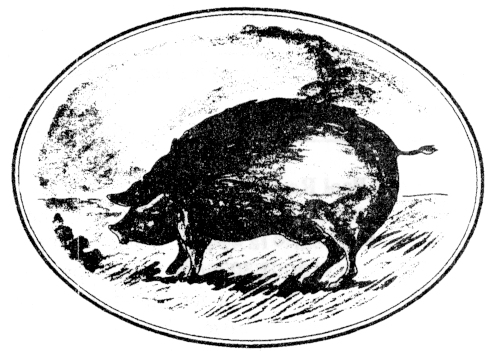

A large docile animal with snub nose and dish face, this good natured creature responds well to comfortable conditions and generous rations, making it disinclined to root and wander.LARGE BLACK

Once widespread in Devon and Cornwall, this distinctive breed owes its black coat to a Neapolitan ancestry. To this day it is highly valued for the sow's excellent mothering qualities.

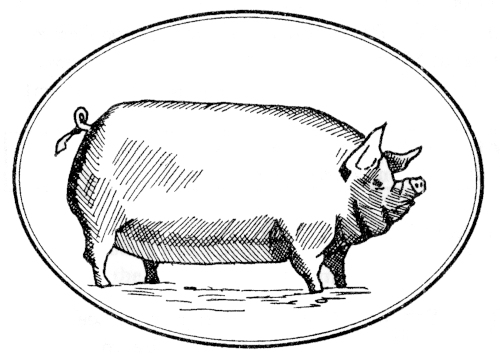

SANDY AND BLACK

With a lineage going back centuries on the farms of the Midlands, this is a good all purpose, hardy animal. Regrettably, a tendency to produce small litters has threatened its survival.TANWORTH RED

Prick eared, long backed and narrow in build, with a long straight snout, the Tamworth exported well to sunny climes as its dark red colour offers excellent resistance to sunburn.

Illustrations by: Paul Swailes

28

SEASONAL RECIPE

Christmas Fruit

Cake

- 1 cup water

- 4 large eggs

- 2 cups dried fruit

- 1 tsp baking soda

- 8 oz nuts

- 1 cup sugar

- 1 bottle Malt Whisky

- 1 cup brown sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- juice of 1 lemon

Directions:

- Sample the whisky to check for quality!

- Take a large bowl. Check the whisky again, to be sure it is of the highest quality!

- Pour one level cup and drink. Repeat.

- Tum on electric mixer, beat one cup of butter in a large fluffy bowl. Add one tsp sugar and beat again.

- Make sure the whisky is still O.K. Cry another tup.

- Turn off the mixerer.

- Break two eggs and add to the bowl and chuck in the dried fruit. Mix on the turner. If the dried fruit gets stuck in the beaterers, pry it loose with a drewscriver.

- Sample the whisky to check for tonsisticity.

- Next sift two cups of salt, or something. Who cares?

- Check the whisky.

- Now sift the lemon juice and stain your nuts. Add one table. Spoon. Of sugar or something. Whatever you can find.

- Grease the oven.

- Turn the cake tin to 350 degrees.

- Don't forget to beat off the turner.

- Throw the bowl out of the window.

- Check the whisky again and go to bed.

Anne Bailey

Thanks Anne for the tip!

Bad luck, Brian, no cake again this year!

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

30

OGDEN NASH [1902-1971]

American author whose numerous volumes of humorous verse are characterised by puns and unorthodox rhymes. His work displays remarkable skill and ranges in tone from acid satire to genial nonsense.

The cow is of the bovine ilk;

One end is moo, the other, milk.

Tell me, O octopus, I begs,

Is those things arms, or is they legs

I marvel at thee, Octopus;

If I were thou, I'd call me Us.

Behold the duck.

It does not cluck.

A cluck it lacks

It quacks.

It is specially fond

Of a puddle or pond.

When it dines or sups,

It bottoms ups.

The pig, if I am not mistaken,

Supplies us sausage, ham and bacon.

Let others say his heart is big -

I call it stupid of the pig.

The firefly's flame

Is something for which science has no name.

I can think of nothing eerier

Than flying around with an unidentified glow on a person's posteerier.

I don't mind eels

Except as meals

And the way they feels.

Some Primal termite knocked on wood

And tasted it, and found it good,

And that is why your cousin May

Fell through the parlour floor today.

Illustrations by: Paul Swailes

13

A BACKWARD GLANCE

They sat on the sand dune together, yet apart with their own thoughts, watching the waves break on the shore, just a few hundred years from where they had camped with their children more than a quarter of a century ago. He remembered the large black ants that had invaded the sugar, and heard the echoes down the years of his wife saying, as she handed round the mugs of tea, "One ant or two?" The sound of the long ago laughter drifted on the wind.

Five ghosts passed by, splashing along the water's edge - two girls, a boy, a man carrying an inflatable dingy, and his young wife, all making their way to the mouth of the estuary. He watched as the man towed the boy in the dinghy through the shallow water over a sand bank that gave the impression that he was walking on water, which caused much laughter from the onlookers.

The double-decker bridge looked just the same - road on top, railway underneath - the railway that ran up to the station, where he took his youngest daughter and the young lad for his birthday treat, a ride on a Portuguese train. He sat there staring into the past, sad of soul and moist of eye. "Dear God, where had the time gone?" He loved them all so very, very much, but had never been able to convey to them his deep love, they meant more to him than life itself.

"Time we were going, dear" his wife said, and he stood and helped her to her feet, to retrace their steps wearily over the dunes.

Laurie Harvey

Illustrated by: Nigel Mason

16

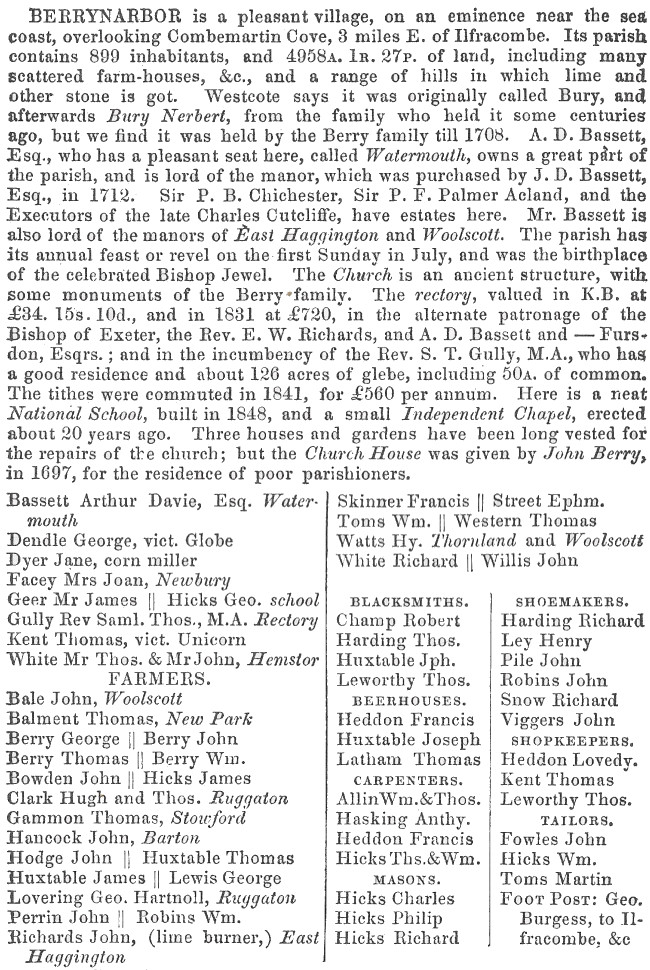

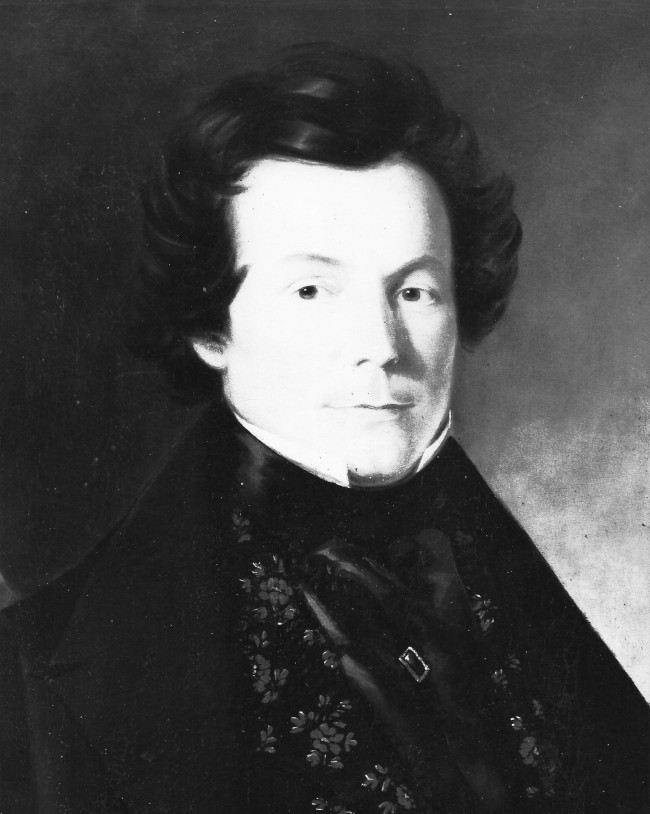

KEEPING IT IN THE FAMILY

I wonder how many readers have come across "White's 1850 Devon"? If you have, you will know that this Directory of 1850 "has long been recognised and used as one of the major source books for the local historian in Devon. It is a veritable mine of information on towns and villages, industries and agriculture, ports and inland communications, customs and charities. Much can be learnt even from the list of traders and leading citizens in each town and village."

Reproduced below, by kind permission of David and Charles, Publishers, Newton Abbot, Devon, from White's Devon by William White, 1850, is the entry for Berrynarbor.

In compiling this Directory, as in the compilation of his other directories [Suffolk 1844/1855, Norfolk 1845, Lincolnshire 1856, Yorkshire I & Il 1837 and Hampshire 1859] William White and his assistants claim that "every parish and almost every house in this extensive county has been visited."

Little is known about William White except that his involvement with directories began in Newcastle in 1829. He moved to Sheffield in 1830 and began publishing on his own account, mainly covering the northern and eastern parts of England. His Devonshire Directory was his first venture outside these areas, but the reason for this was unknown. At some time, William White was joined by his son, also William, who took over on his father's death in 1868. However, he did not survive his father long, dying two years later in 1870, when the business was taken over by his brother.

It is interesting to note from the entry that many of the names given are the same as those of today's residents, presumably they may be their great-great [or even great] - grandparents! Although I cannot claim any of them to be my relatives, I can, however, claim that William White was my great-great-grandfather; my mother, Barbara Pickup, nee White, being his great-granddaughter. As a family, we have no further information on him, but a copy of his portrait [the original being in the possession of a distant cousin] hangs in our sitting room.

White's Directory is now out of print - a reprint was published in 1968, but copies are available in the local libraries and an original, published in 1850, is in the Ilfracombe Museum.

Judie Weedon

13

BLACKBERRY PICKING FAIRIES!

The long, hot summer has been responsible not only for a fine crop of blackberries, but also for a not-so fine outburst of poetry in the village. It all began with my finding a bag of those luscious berries outside my front door, together with a note:

"The fairies thought that you might like

These blackberries we picked last night."

Intrigued, I asked one of our visitors, "Do you know anything of blackberry picking fairies?" From his expression it was obvious he didn't! A second visitor was disappointed to find it was not the opening to a Devon fairytale. Light dawned - it was the style and kind thought of a good friend. A 'phone call revealed I was wrong again.

I made bramble Jelly next day. That evening I returned to find a second bag of blackberries on the doorstep and another note:

"lt ain't no fairy with dainty wings,

Just a clumsy lass wot falls over things!

But no fairy nor elf will ever beat me

At blackberry picking as you will see.

Please accept these fruits from - an O. A. P."

Now, I've not penned a poem since the daft days of limericks, but couldn't resist dashing off:

"The fairies - instead of watching 'telly'

Turned blackberries into bramble jelly! Magic!

What's more the glorious dawn revealed

Some mushrooms in the field.

The fairies took no time to send

These country fruits to my kind friend."

... and delivered it to said 'kind friend' with a jar of juicy jelly and a fistful of field fungi.

The fairies then had a field day. A sweetly scented posy of roses arrived with:

"The village fairies have dried their wings,

They use silver birch pegs for these delicate things!

Now they are flying all over the place,

Chasing the swallow - quite a race.

Whilst having a breather they picked these roses

Which they then turned into delightful posies.

These they offer to Middle Lee

For sending mushrooms and jelly for tea."

We called a truce - well, I did. I couldn't better that. The only person to get nothing out of this 'cultural exchange' - other than a good laugh - was GRACE, yes, Nipper's Grace.

Three days later she asked if l'd found the blackberries. What a good fairy!

Pam Parke

12